I had the pleasure of taking a class on Cyanolumens with The School of Light in December. I’ve made lumen prints, I’ve made cyanotypes, but somehow the combination of the two was never something that clicked in my brain. Merging standard silver gelatin with “alt process” seemed enticing.

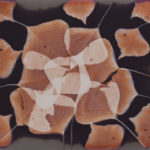

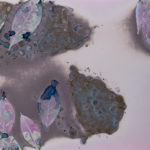

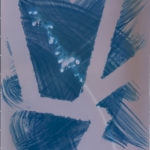

We started with some basic lumen prints, where I was able to explore the color palette of a variety of papers. The added blue/green/yellow of cyanotype made for an expanded range of colors depending on which papers I used. The process also allowed me to travel down the rabbit hole of questioning when is photography a document of another object, and when is photography the art itself? As an artist who deals with photographic paper as an object, I had to reconcile the impermanence of the lumen print with its documentation, and allow that to be art itself. I can’t say that I am pleased that the final art object would be an inkjet print, but it is what it is. My eyes saw the finished result — the wild range of colors that rivals a chemigram — and my documentation clings to that reality as best as I could reproduce it, without added drama of contrast or saturation.

These thoughts interestingly coincided with a great conversation I had as part of Cameraless Photography Month with the Experimental Photo Festival in Barcelona, Spain. My breakout room question dealt with what the relationship is between cameraless photography and The Decisive Moment — namely that there seems to be a lack of such moments without the presence of a shutter in the artist’s toolbox. As a chemigam artist, I found myself comparing The Decisive Moment, as Henri Cartier-Bresson might have defined it, to the moment you know a certain resist is about to disappear, and how I can achieve a color or a pattern based on the progression of chemical steps. I have learned to somewhat control the chemigram process to achieve compositional goals. And similarly, the documentation of a lumen print boils down to a particular knowledge of what will happen to a composition given a certain amount of time and exposure to light. I began to understand how a print would change if I didn’t document it immediately, or how the composition might shift in my favor if I waited.

Subject-matter-wise, I really appreciated the opportunity to be able to scour the grounds of my home and acquire plants as a way to document my immediate environment. This seemed particularly fitting during a pandemic — while we aren’t formally in a lockdown in Georgia, my household basically is, due to pre-existing conditions. The last time I freely left my house without concerns was March 13, 2020. I’ve gone through various waves of acceptance and wanting to jump out of my skin over our isolation. But I felt grateful making these lumens — the fact that I have some land to wander during this isolated time — less than many, but much more than those locked away in apartments in urban centers. I can also be grateful to live somewhere that still has some green in winter, something alive, something growing in the month of December. I was able to harvest a handful of ferns trying to squeeze their way through the cracks of the back deck, my stubborn Mexican Petunias, a yard of clover, various unnamed volunteers, and even one last struggling tomato plant who gave two more fruits before the class concluded. The fact that these objects touched the paper, rather than relying on the intermediary device of a camera, that these plants were dealt the fate of blooming during this incredibly difficult year, make these prints as objects even more precious. Perhaps the fact that the print-objects can only be viewed briefly, under low light, like some of the first photographs ever made, is fitting for the slowing-down of life we’re experiencing at this time.