I am a fan of details. Sometimes this works in my favor. Sometimes this paints me in an unflattering light.

I hear the concerns of artists who state that they don’t want to define themselves, to be hemmed in by an artist statement, or who don’t want to place their artwork in an easily-labeled box. They flirt with various media, accessing one when necessary, avoiding technical control, often on purpose. I am an educator, so I do understand these concerns. I see a place for this handling of media; I know not everyone embraces words. The educator in me can see the tide shifting, and is learning to respond.

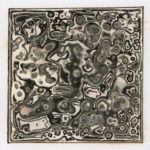

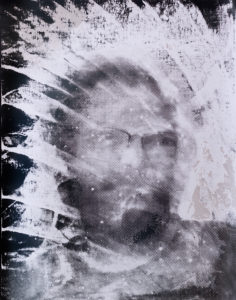

But as an artist, I start thinking about the details — my voracious and nerdy satisfaction in learning the steps of a process, the materiality of an artwork, the dance between control and chaos, and how all of that ties to concept. I think about the ways I’ve connected with others through the bantering and bonding over these details. These details require time and effort.

I first started noticing something awry with the #chemigram hashtag in early 2022.

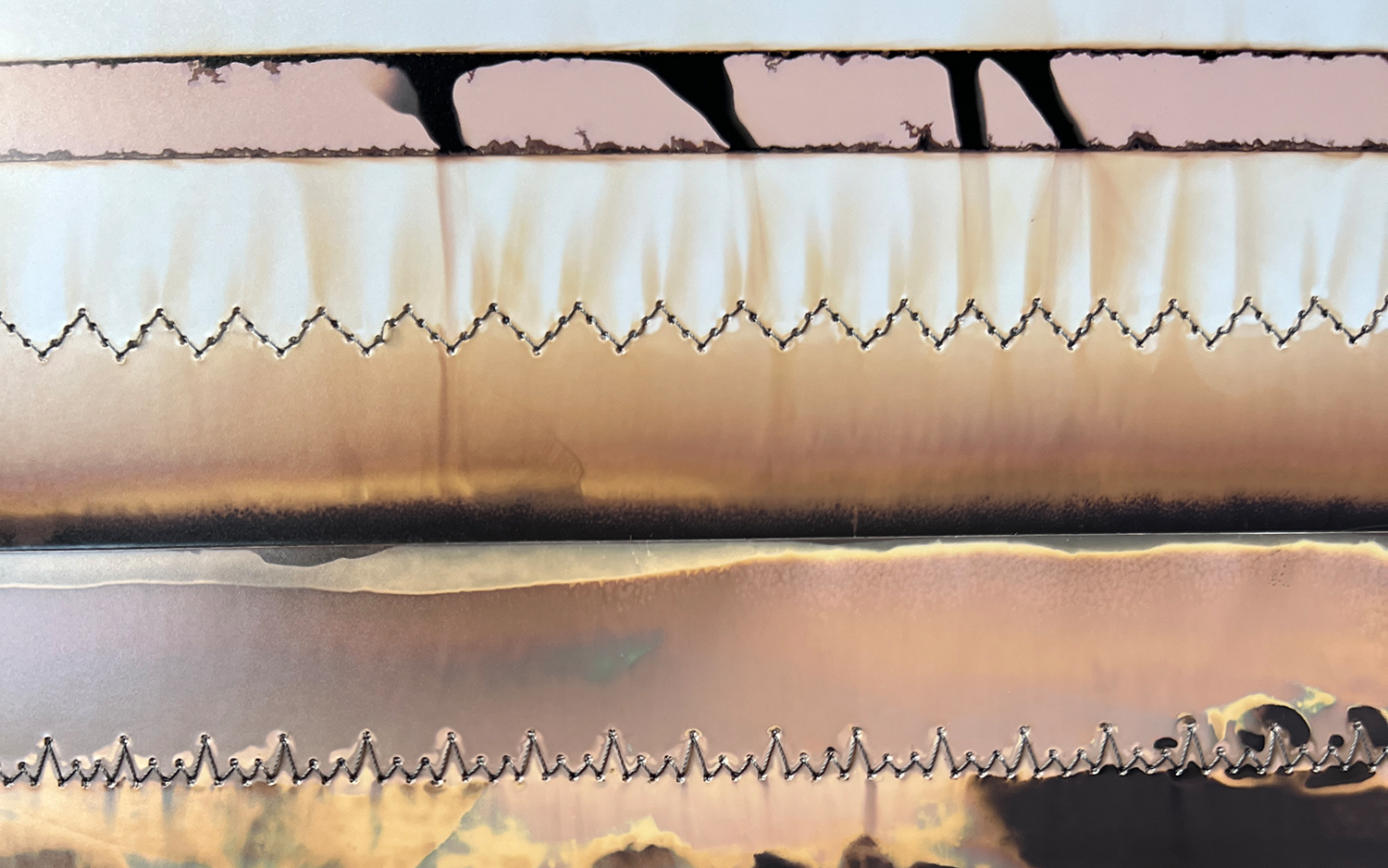

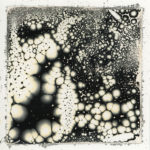

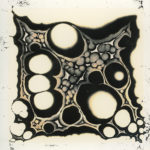

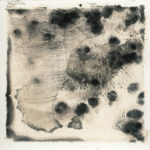

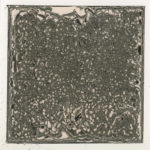

I’ve been swimming in the waters of chemigram experimentation for many years now. I’m always interested in seeing who is out there exploring this elusive medium. Seasoned experts, beginning students, and everyone in between – I love discovering what others are finding in this process that continues to provide awe and wonder in my own life.

It started with the lumen prints being tagged as #chemigrams. Then the photograms. Then, basically any traditional silver gelatin print that came out of a darkroom was tagged as a #chemigram. After witnessing this repeatedly, socks started growing over my feet, sandals appeared over them, my fist mechanically arose into the air, the words “get off my lawn” expelled from my frustrated mouth. None of these were examples of chemigrams, dammit.

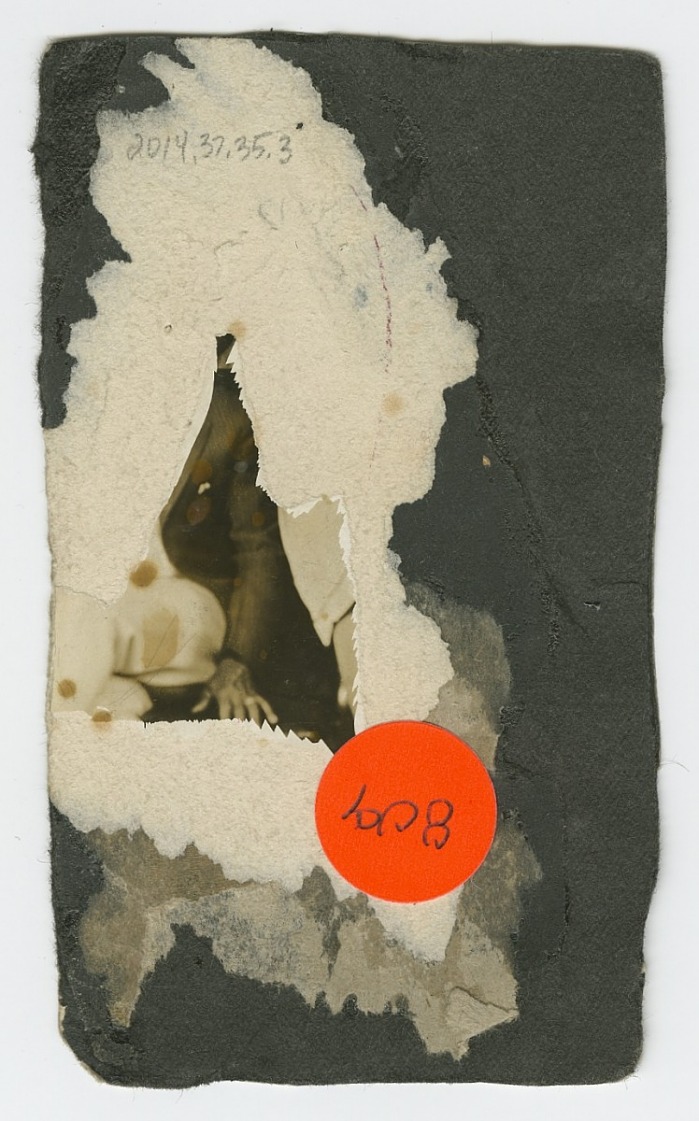

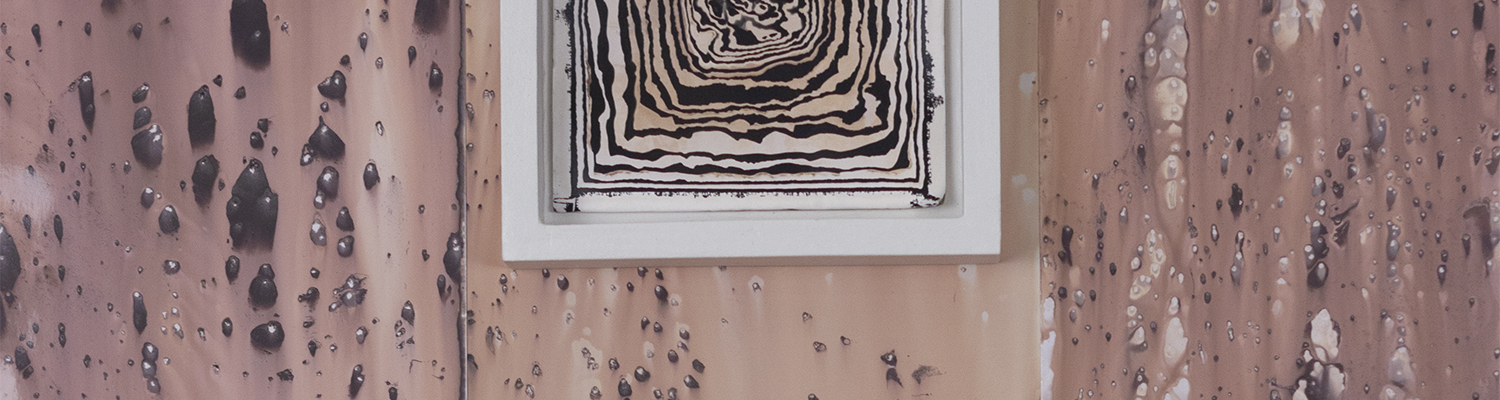

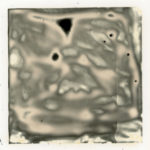

Around the same time, I started noticing instances of acclaimed photographic artists presenting exhibition works where the medium and process were misrepresented, or side-stepped altogether. A chemigram that was defined as a “digital print”; a pigment-print documentation of lumen that was presented as light-sensitive silver gelatin paper. A complete lack of media definition from a photographic artist – although I’ve never heard of a painter who defined their medium as “painting” — I see this all the time in the photographic world.

As my little pot of obscure anger began to boil over, I transitioned into the question, “why does any of this matter to me?”

Let people mislabel things, Bridget. It doesn’t make anyone evil. So what if a photogram isn’t a chemigram and a “digital print” isn’t even a medium. Your students are going to use that term no matter how many times you basically beg them not to. Let people have nice things. Relax, you jerk.

Ohhhhhhh, but the details.

The details are where we bond, where we argue, where we find our people. The details are where we connect to a shared identity, to people who have struggled over the same process, where we have spent hours or days failing and learning together despite being miles or continents apart. We’ve both been stained by silver nitrate, we’ve both labored in the same dimly-lit room over loud music, we’ve both put in the time.

And I want to see that reflected in the art object you’re presenting to the world.

There are reasons to make pigment prints of your original light-sensitive works, but please call them for what they are. I can appreciate them for what they are.

But personally, if given a choice, I prefer to spend time standing in front of your original light-sensitive print, your unique physical object, and I want to make that connection to YOU – the artist, not the print. I want to look at it and sense that we wrestled with the same problems, we learned together, we were both in awe together. The print before me is evidence to that shared experience.

Epson ink doesn’t exactly convey those emotions to me. (Sorry, Epson.)

And I guess that’s why I get so grumpy with a misused #chemigram hashtag. It’s an implied bond that just misses the mark. It’s the implication that you’ve made an object that has the audacity to take up space in this overly-digitized world, that you’ve danced with the same variables and can connect to that same sense of wonder, just for me to learn that’s not quite true.

I’m learning to not get as annoyed as I was upon seeing wild uses of #chemigram. Everyone has to learn. Heaven knows I was a totally ridiculous student. And I do have to accept that some people aren’t as precious about the details.

But I do hope us photographic artists will all start better-respecting the physicality of the photographic medium. From glass plates, to plastic-coated paper, to electrons, the pendulum has swung and we are back to being object-makers. I hope we can all get better-attuned to appreciating materiality, and celebrating the art object that is the photographic print. Experimental photographic imagery can provide endless “cool” visuals, but I long for the particulars that provide human connection forged through time and commonality. I want to see the print that took this journey with you. Or at least be told if I’m seeing something other than that.

And because of this, sometimes a #chemigram just isn’t a chemigram.